Spotlight: Godwits adjust to climate change – humans must too

Climate change will test animals’ abilities to adjust and adapt to a rapidly changing world. So, if you heard that shorebirds were able to adjust their reproductive behaviour in response to climate change, you’d think that was a good thing, right? So would I. In this issue of Wader Study, Nathan Senner and colleagues, studying Black-tailed Godwits Limosa limosa limosa in Dutch meadows, illustrate that in years with extreme weather godwits can exhibit breeding behaviours beyond what has been documented historically1. There is just one catch – if we humans don’t adjust our behaviour in tandem, no amount of adjustment on the part of shorebirds will suffice.

Black-tailed Godwits have been studied in the Netherlands since the 1950s, and their population has been in dramatic decline for the past few decades. During the 2013 and 2014 breeding seasons, Senner and colleagues intensively studied godwit reproductive biology in and around the Haanmeer Nature Reserve in SW Friesland. The researchers attempted to find every nest in a 1090-ha area and to ring at least one breeding adult and all chicks at each nest. Their work was embedded within a long-term demographic study in which researchers are ringing and monitoring godwits over a 10,000 ha area 2. Because godwits have been studied in the area for so long, Senner and colleagues were able to compare their 2013 and 2014 data on breeding biology to historical data.

As it turns out, 2014 was an abnormally warm and wet year in the Dutch meadowlands. Without humans in the picture, warm and wet years provide ideal conditions for godwits; vegetation grows quickly, providing cover, and insects are plentiful both before and after chicks hatch. In 2014, Black-tailed Godwits responded by intensifying and extending their breeding efforts. They re-nested more often – both after predation, and after nests had been damaged by agriculture – and they extended their breeding season to a record 57 days. One pair even started a nest on 4 June – the latest nest initiation date on record.

Good news, right?

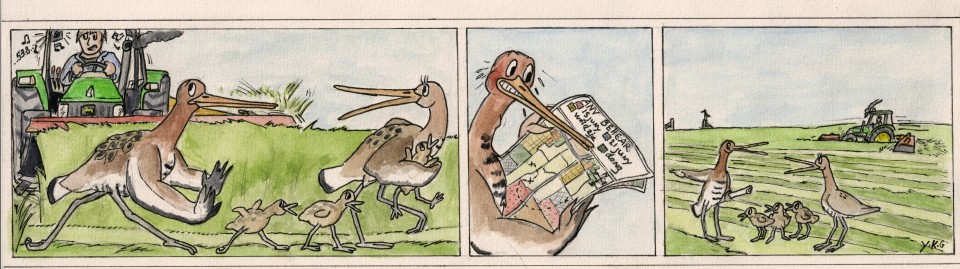

Well, not if the godwits are nesting in meadows that will be mowed for agricultural purposes. Fast grass growth means that farmers working outside of nature reserves mow their meadows earlier and often – sometimes five or six times in a season! A mowed meadow means no cover and no food for godwit families. Although farmers will mow around marked nests for conservation purposes, a stand of tall grass in a mown meadow attracts predators.

Things are better for godwits in nature reserves like the Haanmeer where Senner and colleagues worked. Farmers within these reserves work with the Staatsbosbeheer (the Dutch governmental land manager) to avoid early mowing in fields that have chicks. However, a much larger area of land is owned by private farmers. Some private landowners are environmentally minded and will take agri-environmental subsidies in exchange for waiting until 15 June to mow their fields. This policy is based on historical data and assumes that most chicks will have fledged by this date. But when godwits extend their breeding season, their eggs do not take less time to mature. On 15 June, nests laid after 25 April will still have chicks, and nests laid after 20 May will still have eggs. So if humans don’t adjust with godwits, then an extended godwit breeding season is very bad news.

Godwits can adjust their behaviour in response to climate change. This flexibility (reversible adjustments made during a lifetime and not incorporated into the DNA sequence) is not yet genetic evolution. Yet, these adjustments can be passed onto the next generation. Epigenetic processes within cells allow life’s experiences to alter the way genes are expressed in current and future generations 3,4. Physiological changes can be passed on via developmental inheritance (e.g., through maternal hormone affects) and behavioural changes can be passed on as younger individuals learn from older individuals through cultural inheritance 3. Senner and colleagues were not studying the mechanisms behind how flexibility in godwit breeding behaviour might be passed on. What is clear from their study is that godwits nesting longer and later in favourable seasons could produce more offspring in the next generation than those who do not seize this opportunity. However, if godwits breeding later suffer lower breeding success due to human behaviours, these potentially positive adjustments to climate change might be strongly selected against. Inheritance of adaptive traits – by any mechanism – is snuffed out if the next generation does not survive.

So how flexible are humans? Can we adjust as fast as the godwits?

_____________________________________________________________

1 Senner et al. 2015. Just when you thought you knew it all: new evidence for flexible breeding patterns in Continental Black-tailed Godwits. Wader Study 122(1): 18–24.

2 Kentie, R. 2015. Spatial demography of black-tailed godwits: Metapopulation dynamics in a fragmented agricultural landscape. PhD thesis, University of Groningen, NL

3 Piersma, T. 2011. Flyway evolution is too fast to be explained by the modern synthesis: proposals for an “extended” evolutionary research agenda. Journal of Ornithology 152: 151-159.

4 Hughes, V. 2014. Epigenetics: The sins of the father (News feature). Nature 506: 22-24.

* Reproduced with permission from Ysbrand Galama. https://www.bornmeer.nl/winkel/de-skriezemaaitiid/